A Blind Eye On Women

http://commentisfree.guardian.co.uk/nadje_alali_/2008/03/a_blind_eye_on_women.html

On International Women's Day in 2004, nearly a year after the invasion of Iraq, George Bush, the US President, addressed 250 women from around the world who had gathered at the White House. "The advance of women's rights and the advance of liberty are ultimately inseparable," he said. Supported by his wife Laura, who herself hailed the administration's success in achieving greater rights for Afghan women, the president claimed that "the advance of freedom in the greater Middle East has given new rights and new hopes to women there".

Advance. New rights. New hopes. Stirring stuff, but totally empty claims. In fact, Iraq's women have become the biggest losers in the post-invasion disaster. While men have borne the brunt in terms of direct armed violence, women have been particularly hard-hit by poverty, malnutrition, lack of health services and a crumbling infrastructure, not least chronic power cuts which in some areas of Iraq see electricity only available for two hours a day.

Over 70% of the four million people forced out of their homes in the past five years in Iraq have been women and children. Many have found temporary shelter with relatives who share their limited space, food and supplies. But this, according to the UN refugee agency, has created "rising tension between families over scarce resources". Many displaced women and children find themselves in unsanitary and overcrowded public buildings under constant threat of eviction.

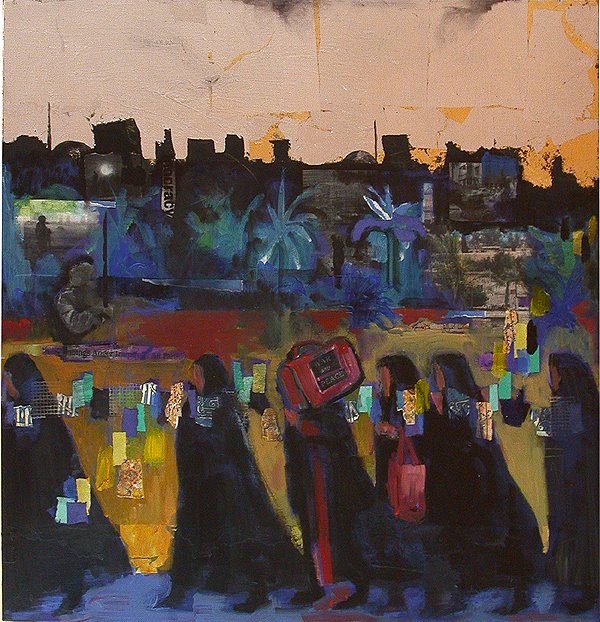

Meanwhile, rampant political violence has also engulfed women in Iraq. Islamist militias with links to political parties in government and insurgent groups opposing both the government and the occupation have particularly targeted Iraqi women and girls. A new Islamist puritanism is seeing women and girls being violently pressured to conform to rigid dress codes. Personal movement and social behaviour are being "regulated", with acid attacks (deliberately designed to disfigure "transgressive" women's faces), just one of the sanctions of the new moral guardians of post-Saddam Iraq.

Suad F, a former accountant and mother of four children who lives in a previously mixed neighbourhood in Baghdad, was telling me during a visit to Amman in 2006: "I resisted for a long time, but last year also started wearing the hijab, after I was threatened by several Islamist militants in front of my house. They are terrorising the whole neighbourhood, behaving as if they were in charge. And they are actually controlling the area. No one dares to challenge them. A few months ago they distributed leaflets around the area warning people to obey them and demanding that women should stay at home."

By 2008, the threat posed by Islamist militias and extremist groups has gone far beyond dress codes and calls for gender segregation at universities. Despite - or even partly because of US and UK rhetoric about liberation and women's rights - women have been pushed back into their homes.

Women who have a public profile - as teachers, doctors, academics, lawyers, NGO activists or politicians - are now systematically threatened, seen as legitimate targets for assassinations. Criminal gangs have joined in. Though rarely reported in Britain, the criminal kidnapping of women for ransom, for trafficking into forced prostitution outside Iraq, and for out and out sexual abuse have all taken root in post-Saddam Iraq.

Killings in Basra in 2007 provide a snapshot. According to a study by the Basra Security Committee, 133 women were killed last year in the UK-controlled city, either by religious vigilantes or as a result of so-called honour killings. Of these, 79 were deemed to have "violated Islamic teachings", 47 were killed to preserve supposed family honour, and the remaining seven were targeted for their political affiliations. As Amnesty International said last year, "politically active women, those who did not follow a strict dress code, and women [who are] human rights defenders are increasingly at risk of abuses, including by armed groups and religious extremists."

The invasion and occupation of Iraq has also directly added to suffering of women. While aerial bombings of residential areas have been responsible for thousands of civilian deaths, many Iraqis have lost their lives while being shot at by American or British troops. Whole families have been wiped out as they approached a checkpoint or did not recognise areas marked as prohibited.

In addition to the killing of innocent women, men and children, the occupation forces have also been engaged in other forms of violence against women. There have been numerous documented accounts of physical assaults at checkpoints and during house searches. American and British forces have also arrested wives, sisters and daughters of suspected insurgents in order to pressure them to surrender. Recent figures show that the US and Iraqi forces are currently holding (mostly without charge) many thousands of detainees, and even where women have not been detained as bargaining chips they have spent frantic months or even years trying to discover where their family members were being held and why.

Women in Iraq suffered from discrimination and violence well before 2003. Deep-rooted patriarchy (especially in rural and tribal areas) and the pervasive repression of all women politically resistant to Saddam's Ba'athist project were hallmarks of life in Iraq in the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

But there were subtleties which gave women relative freedom. First, Saddam's political acuity meant that he was perfectly capable of a policy of "state feminism" that partly shifted patriarchal power away from fathers, husbands and brothers, investing this power in the state itself - Saddam himself becoming the father of the nation. As long as you steered clear of all oppositional politics, this created 20 years (from the late 1960s on) of moderate liberty for at least Iraq's urban middle-class women.

Then, with the growing militarisation of Iraq after the Iran-Iraq war and the major reverse of the Gulf war of 1991, Saddam switched policy toward cultivating political allegiance through tribal leaders. The upshot for women? A re-assertion of traditional conservative values that saw women's rights used as bargaining chips and their bodies the repositories of tribal and familial "honour".

As he stood before his female audience in 2004 did President Bush actually understand any of this? Was it factored at all? Or instead, did the US's infamous lack of post-invasion planning include a blind spot over women's rights? Perhaps George and Laura would like to update us.